Mirror Mirror On The Wall, Which Is The Fairest Diet Of Them All?

The Most Current Understanding Of How To Eat For A Happy And Healthy Life

Introduction

It is widely accepted by health experts across the world that diet is a key driver of health and disease. Nutrition science has advanced dramatically in recent years, prompting many of my patients and readers to ask for an updated, comprehensive dietary strategy for optimal health—one that includes recipes, shopping lists, and simple-to-follow rules and concepts. Short of writing a book, that’s a tall order, but I will attempt to provide an abbreviated version in this Health and Science Briefing.

I. General Considerations

It is appropriate to begin by acknowledging that we are as yet far from achieving a unified expert consensus on what exactly constitutes an optimally healthy diet. This Briefing represents my best effort to convey the story that the medical and scientific research have been telling us over the last two to three decades. We’ll begin with the big picture, and then gradually drill down to the details.

II. The Big Picture Concept of a Healthy Diet

Our discussion begins with a quick glimpse through the lens of evolutionary biology. Humans evolved as a species over millions of years in tandem with a relatively stable diet that was high in fiber, low in sugar, and teeming with microorganisms. Much of what our ancestors ate was raw. And they consumed their food in a manner that can be best described as feasting and fasting, bringing down an animal or clearing a thicket of berry-laden bushes and gorging, then going without until the next big opportunity. I refer to this type of food and eating pattern collectively as the evolutionary human diet (EHD).

In the last hundred or so years (the blink of an eye in evolutionary time), what and how we eat has migrated quite far from the EHD, and part of the story that the research has been telling is that we are now paying a steep price for that in terms of our health. Simply speaking, we are not evolutionarily adapted to the standard American diet (SAD) of today which is dominated by processed foods that are low in fiber, high in sugar and easily digestible starches, and loaded with additives, preservatives, and flavor-enhancing chemicals.

We are also eating more than we ever have. If we include snacks, Americans today eat, on average, four to six times per day. This is unusual behavior from an evolutionary perspective. But it is something that is promoted by many healthcare providers including dieticians, nutritionists, and physicians despite significant data showing that frequent eating/snacking is strongly linked to negative health outcomes and poor dietary habits. It is fair to say that snacking is a well-established contributing factor to obesity and various forms of chronic illness.

And many of these same well-educated and well-intentioned healthcare providers view fasting as a kind of extremist—even dangerous—practice despite enormous evidence showing that regularly going at least 24 hours without calories is one of the most powerful tools at our disposal for promoting good health and longevity.

The world of medicine is like a great ship that turns very slowly. It can take years or even decades for official recommendations and practice guidelines to change in a foundational sense. Often, by the time it does, those recommendations are once again lagging behind the best and most current scientific information.

I look at the way we eat today as a kind of mass experiment that would never have received approval from any responsible investigational review board: What will happen if we suddenly remove a population from a diet and pattern of eating to which their bodies have become extremely well adapted over millions of years of evolutionary history and start feeding them instead (four to six times a day) a diet dominated by hyper-delicious and addicting processed foods laden with preservatives, stabilizers, and flavor-enhancing chemicals to which their bodies have had little or no evolutionary exposure? The data that have emerged from this ‘experiment’ over the last few decades is not good news for the more than two hundred million Americans unwittingly enrolled in the study…

In a Nutshell

In the simplest terms, a return to the EHD’s basic structure of a high-fiber, low-sugar/rapidly digestible starch diet, in combination with regular fasting, while also taking advantage of access to certain probiotic-rich and nutrient-packed foods sourced from all over the world (one of the wonderful advantages of modern life) represents, in my view, a kind of broad-strokes outline for an optimally healthy diet.

(If you’ve noticed that I’ve left fat out of the discussion so far, don’t worry, I will address it later in some detail; for now, I’m just sowing some seeds for thought.)

I call this simply: the Human Diet (HD), and it is something I have been promoting, in progressively updated forms, for more than thirty years with patients who've expressed interest in their health beyond simply overcoming an injury or getting rid of a pain problem. Thanks in part to the astonishing availability of information that is now at our fingertips, each year a larger share of my patients are becoming interested in developing a rational, science-based lifestyle strategy that can extend their lives, improve their overall health and happiness, and help them to look their absolute best.

Can the process of aging be slowed through adapting the HD? Can we lower our risk of developing chronic diseases, improve our energy levels, lift our moods, and enjoy better mental clarity by eating the right way? According to the best and most recent scientific data, the answer appears to be yes. What we eat can tamp down inflammation or gin it up; stabilize or dysregulate our blood sugar levels; induce fat burning or fat storage; increase or decrease our sensitivity to insulin; deepen and broaden our gut microbiome or shrink and narrow it; turn on/up-regulate longevity genes or turn them off/down-regulate them… The HD nudges us toward a positive outcome in each of these metrics, giving us control over our health and beauty in a way that our ancestors could not have imagined.

III. How Our Diet Impacts Our Health

There is no system of our bodies and no aspect of our health that is not influenced by what and how we eat. Millions of Americans are literally making themselves sick by eating a SAD to which they have become gradually and unwittingly addicted. And many or most of the most common health conditions that ail them can be controlled or cured by adopting the HD. This is not a theoretical consideration but a routine observation in my clinical practice.

Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that the U.S. spends nearly twice as much on healthcare compared to the average OECD country, yet we have the highest chronic disease burden. The obesity rate in the US is twice the OECD average and we have the highest number of hospitalizations from preventable causes as well as the highest rate of avoidable deaths among OECD member countries.

But even the astronomical costs associated with medical diagnostics and therapeutics, hospitalizations, and high morbidity and mortality rates don’t provide a complete picture of the real burden of chronic illness on society. The US’s astonishingly high chronic disease burden blunts our workforce productivity and impinges on individual human happiness in ways that are difficult to quantify.

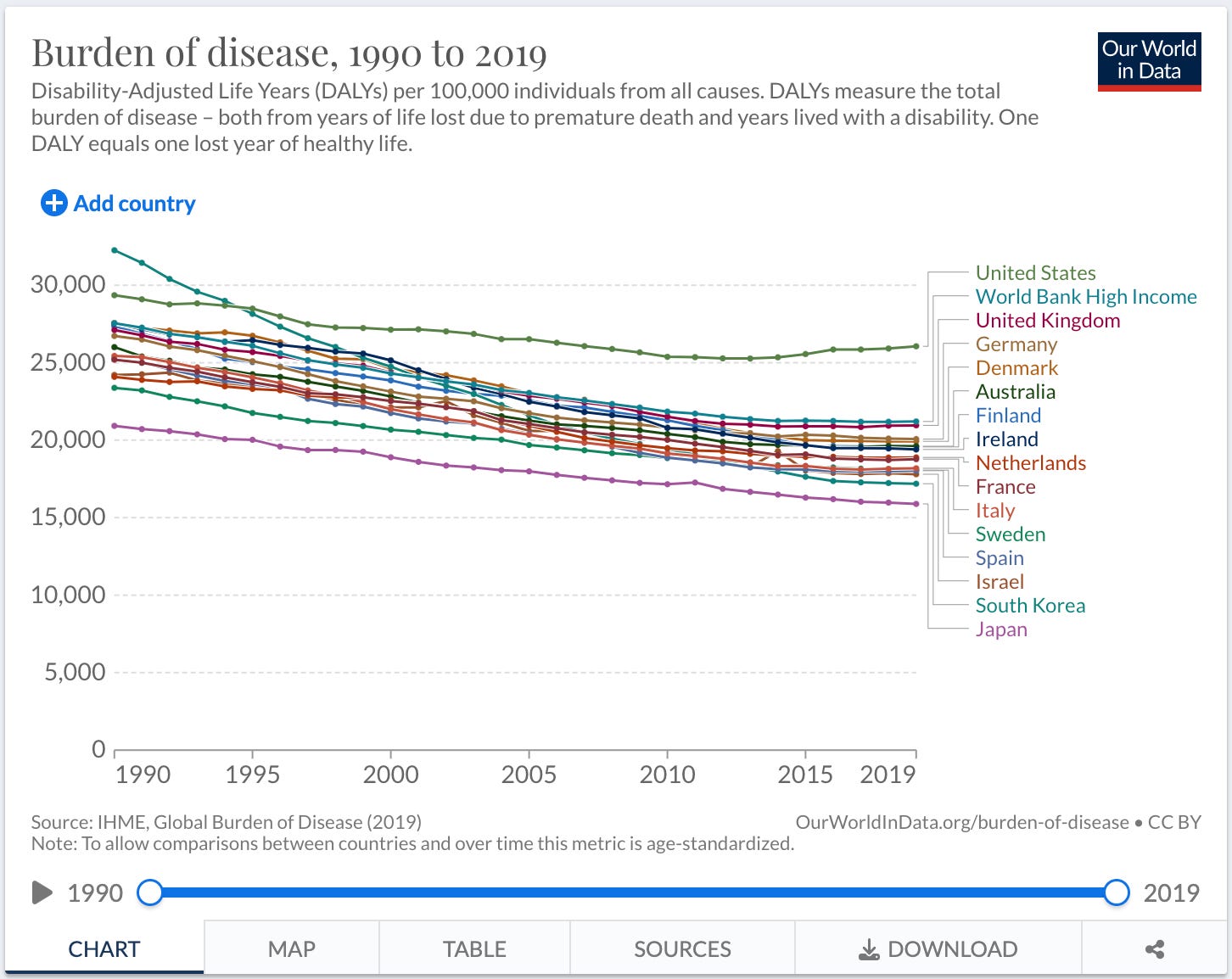

One metric that speaks to this is the disability-adjusted life year (DALY)—a time-based measure that combines the number of years of life expectancy lost due to premature death with the number of years lived in a state of ill health/disability. In essence, each DALY represents the loss of a year of feeling healthy and happy. And we in the US have by far the highest number of DALYs compared to our economic peer nations:

Why is this happening in a country that does the most research, has the most technologically advanced diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, the most robust fitness industry, has extremely well-trained healthcare providers, does an exceptional job of screening for common diseases, and spends more per capita on healthcare than any other nation on earth? There is no single answer that fully explains what’s going on in the US, but two factors stand out as key drivers of DALYs.

The first is that our healthcare system is structured to focus almost exclusively on catching and treating diseases, not on promoting a lifestyle that prevents them from developing in the first place. Having a mainly reactive healthcare philosophy makes little sense to me. There is an old adage: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure…

The second critical factor driving DALYs in the US is our diet which has migrated further away from the EHD than perhaps any other country on Earth. We are eating too much and too often. We eat for pleasure. We eat to reward ourselves for making it through the day. And what we’re eating has changed so drastically over the last century that we are no longer genetically well-adapted to much of the food going into our bodies.

For millions of years of pre-human and human evolution, no food existed that approximated candy, soda drinks, sandwiches, cereals, nacho cheese tortilla chips, pizza, doughnuts, ice cream, or any number of other calorically dense, nutrient-poor processed food items that make up the bulk of what’s on our supermarket’s shelves… Many (most) of the foods in the SAD are chock full of sugars, rapidly digestible starches (which quickly turn to sugar when swallowed), and chemical compounds that our bodies simply do not know how to make good use of. It’s no wonder that we are experiencing a national obesity crisis with an estimated 42% of Americans now categorized as not just overweight but clinically obese.

At the same time, without broad pushback from the medical and allied health professions, we have developed a national habit of recreational snacking on products scientifically engineered to make them irresistibly delicious. Such foods, which induce the release of addicting pleasure hormones in our brains, degrade our ability to appreciate and enjoy the subtle deliciousness of natural whole foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, skewing our palates in favor of ‘junk foods’ including many that are marketed to us as so-called ‘healthy options,’ such as protein bars, juices, whole-wheat bread, and fast-cooking oatmeal…

A Brief History Of Diets

I. The Evolutionary Human Diet

Our evolutionary predecessors evolved over millions of years on a diet of barks, roots, grasses, leaves, berries, nuts, and other fiber-dense vegetation that formed the bulk of what they ate when weather conditions were not too wet, dry, hot, or cold. Many foods were consumed raw which required a lot of chewing and lowered their functional caloric density (cooked foods release their calories more easily during digestion). When they could kill an animal, they would gorge on it until the carcass turned rotten. During the first few years of life, our ancestors drank water and mother’s milk but after that, they drank only water. And throughout our evolutionary history, virtually no prehuman or human animals consumed sugar except for the kinds that occur naturally in fruits and certain vegetables.

Routinely, as a result of weather conditions and/or animal migratory and hibernation patterns, there would be periods of deep scarcity when little or no food was available for days or even weeks at a time. We evolved with a pattern of feasting and fasting from which our bodies learned how to make use not only of the natural, mostly raw foods that were available for us to eat but also of the periods during which there was little or no food at all.

Evolutionarily, our bodies learned how to manage prolonged periods of caloric scarcity by developing an adaptive process of cellular repair and reversal of aging known as autophagy. A day of hunger puts our bodies into survival mode, turning on or up-regulating longevity genes and improving our cellular health (more about this later).

But we have been taught to treat feeling hungry as though it were something bad for us. When I was growing up, my Italian-American mother treated hunger as if it was a kind of medical emergency. If you have never fasted before, ask yourself whether or not you could go a week without food. How about five days? Three days? Many of my patients express doubt as to whether or not they would be able to fast for even twenty-four hours. But I assure you, as with exercise, sauna bathing, cold plunges, and other hormetic practices, the ability to fast routinely in a way that is well-tolerated and even enjoyable is simply a matter of training. But more about that later…

The point is that habitually eating four to six times per day to manage our reaction to hunger sensations or to add to our television-watching enjoyment, in addition to driving obesity, precludes us from ever entering into the true fasting state (which for most people begins at about 24 hours without calories), blocking our access to the reparative, anti-aging benefits of autophagy including turning on or up-regulating longevity genes during periods of fasting.

We’ve Become Obsessed With Cleanliness

In addition to eating too much and too often, throughout our evolutionary history the food that was available to us was covered with traces of dirt! Our ancestors chewed uncooked fiber-dense plant foods, swallowing what they could along with a healthy dose of environmental microorganisms. The lakes and streams from which they drank were teeming with microbes including bacteria, bacteria-like organisms called archaea, yeasts, viruses, fungi, protozoa, helminths, and protists.

Over many hundreds of thousands of generations, the EHD enabled a symbiotic relationship to develop between the myriad microscopic creatures found in the environment and the mucosal cells that line the human digestive tract, ultimately establishing what we refer to today as the gut microbiome (GMB). We populated our GMBs with microbes and sustained them with the fiber contained in the plants that we ate. And those microbes, in turn, fed us with special metabolites produced when they digested that fiber through the process of fermentation.

Over time, our bodies learned to incorporate the many special metabolites produced by fiber fermentation such as short-chain fatty acids (like butyric acid) into the workings of our own physiology to help with gut, immune, and nervous system function and regulation. In short, we became reliant upon the metabolites that only fiber-fermenting bacteria in the GMB can provide. And the human bodies that evolved to need those special metabolites are the same ones that we possess today. However, because our diets have shifted, we are not producing these metabolites in sufficient amounts any longer and this is one way in which the SAD of today is driving poor health outcomes.

So the diet to which we evolved to become ideally genetically adapted was high in fiber and probiotic microorganisms, low in sugar and processed foods, and included regular fasting (defined here as at least 24 hours without calories) which induced autophagy—the body’s self-repair mechanism that reverses cellular damage and slows down the aging process.

II. The Standard American Diet (SAD)

It takes effort to think of ways in which today’s SAD, also commonly referred to as the Western diet (WD), could be more different from the EHD. We’ll get into the details as we go but for now, let’s take a quick look at the two side by side:

It is now accepted science that the SAD/WD is a driver of inflammation and obesity, and that inflammation and obesity are drivers of many of the most common non-communicable diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and even some cancers. Epidemiological research shows that the correlation between the adoption of a WD and rising levels of common chronic diseases in countries around the world is so strong and so consistent that it is difficult to view that relationship as other than causal.

III. Diets Shape Health By Shaping The Gut Microbiome (GMB)

As a reminder, the term gut microbiome or microbiota refers to the more than one hundred trillion microorganisms, including several hundred different species of bacteria, that live within a healthy human intestinal tract. So important to our health is the GMB that most experts now consider it to be analogous to an organ of the body.

In previous briefings, I discussed at length how bacterial species in the GMB help us to mount a strong immune response, maintain brain health, regulate blood sugar, keep our waistlines lean, and even fight off cancers. Recent research indicates that a GMB lacking in certain (fiber-loving) bacterial species and overgrown with other (sugar-loving) species—a condition referred to as a dysregulated GMB or gut dysbiosis— drives the development of depression, autism, irritable bowel, heart disease, and a host of other health conditions, including long-Covid.

So, what causes gut dysbiosis? Five factors appear to be at play:

1. Not enough dietary fiber: Eating foods high in fiber helps lower triglyceride and cholesterol levels, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It bulks up stool for better elimination and acts like a scrub brush, clearing the lining of the digestive tract of old, dysfunctional ‘senescent’ cells capable of turning into cancers. Since we can’t digest fiber ourselves, it makes us feel full without loading us up with calories, which helps to prevent weight gain.

Just as importantly, fiber feeds friendly bacteria in the GMB which, along with producing essential metabolites needed for optimal health, make mucous that forms a protective barrier against infection between the mucosal cells lining the digestive tract and the microorganisms of the GMB.

When we eat a SAD filled with flour-based and sugar laden foods, we don’t consume enough fiber to sustain the metabolite and mucous-producing bacteria in the GMB. Eventually, fiber-loving commensals (species of bacteria that ferment fiber and live symbiotically within our bodies and on our skin) begin to starve and die off, leading to dysbiosis and a thinning of the protective mucous barrier, rendering us more susceptible to infections by both microbes in the GMB and community-acquired bugs including respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza.

2. Too much dietary sugar and rapidly digestible starch: Diets like the SAD/WD that are dominated by high glycemic foods (more about this later) rich in sugar and rapidly digestible starches (especially those found in wheat and corn flour), cause the overgrowth of sugar-loving bacterial species in the GMB. Over time, excessive ‘blooming’ of sugar-loving bacteria pushes out healthy fiber-loving bacteria, promoting dysbiosis. These sugar-loving bacteria also like to eat the protective mucous barrier which makes us more susceptible to infections through the gut.

Interestingly, our intestinal mucosal cells contain some fiber of their own. When the mucous barrier gets too thin due to insufficient dietary fiber and excessive dietary sugar, hungry fiber-loving bacteria in the GMB migrate across the thinned mucosal barrier to invade the cells that line the intestinal tract to harvest their fiber. When otherwise friendly bacteria are driven to invade mucosal cells for survival, this results in inflammation which we experience as painful bloating, diarrhea, and nausea—the typical symptoms of irritable bowel.

So the SAD/WD, because it is low in fiber and high in sugar/rapidly digestible starches, makes us metabolite-deficient, vulnerable to infections, and can cause symptoms of irritable bowel.

3. Emulsifiers in processed foods: There are also data showing that emulsifiers which are common additives to highly processed foods and therefore, abundant in the SAD can shift the microbiome, sometimes in harmful ways. Common emulsifiers found in the SAD include lecithin, maltodextrin, polysorbate 80, propylene glycol, and gums such as guar gum.

4. Excessive cleanliness: The key to an optimal GMB is diversity. Each bacterial species produces its unique metabolites and we need them all (including some of the sugar-loving ones—but more about that later) to function at our best. A healthy, well-regulated GMB contains several hundred different bacterial species while a dysregulated one may have fewer than 50.

Evidence suggests that in order to establish and maintain a wide diversity of bacterial species in our gut, we have to swallow some microbes with the things that we eat and drink. Sanitary practices that reduce the prevalence of food-borne illness constitute one of the most powerful public health measures ever deployed, saving countless lives. I do not counsel my patients to eat foods that have been prepared or stored in an unsanitary manner and can, therefore, cause food poisoning! However, as with everything, there is a sweet spot for cleanliness, and excessive sanitation that prohibits friendly microorganisms from reaching our gut narrows the GMB.

In the summers of my youth, one of my grandfather’s great joys was eating fresh tomatoes from the garden. He’d brush the dirt and spores of pollen off with his giant fingers, open the tomato with a pocket knife, sprinkle a little salt from a shaker he kept in the deep well of his trouser pocket, and eat the sun-warmed tomato just like a fruit straight off the tree. Sometimes he would put thick slices on crusty bread that he had rubbed with a clove of garlic and drizzled with olive oil, add a dark green aromatic basil leaf (also from the garden and brushed ‘clean’ by his fingers), and eat it like an open sandwich. I can still recall him sharing that special treat with me and how delicious it tasted. Looking back, there must have been trace amounts of non-harmful microbes on those unrinsed tomatoes and basil leaves. For virtually all of human evolutionary history, most of what we ate and drank contained a few bugs.

5. Use of antibiotics (ABs): ABs are another jewel in the crown of modern medicine. They are used to treat bacterial infections which, for most of human history, were a leading cause of death. Like sanitary food-handling procedures, the use of ABs has saved countless lives. But ABs don’t kill viruses, and many of the most common infections we get including colds, flu, RSV, and Covid-19, are caused by viruses. According to the CDC, unnecessary and inappropriate AB therapy—such as using them to treat viral illnesses—may constitute as many as half of all AB prescriptions written in the outpatient setting in the US!

When antibiotics are given inappropriately—to treat a cold virus, for example—they cause some collateral damage by killing off some of the friendly bacteria in the GMB without helping fight the infection. This is one reason why good primary care providers are judicious about prescribing ABs for patients who are sick. Even when ABs are administered appropriately to fight a bacterial infection, they can still knock down some of the good bacteria in the gut (as well as in the microbiotas of the mouth, nose, throat, vagina, ears, etc.).

So we can say that our health is substantially impacted by the degree of diversity or the breadth of the GMB which in turn is substantially influenced by three dietary and three non-dietary factors: fiber, sugar/processed foods, emulsifiers, excessive cleanliness, and the use of antibiotics. And it is through this understanding that I have updated my conception of what constitutes an optimally healthy diet. As a ground principle, an ideal diet should support a broad, richly diverse GMB.

IV. Other Diets

Attaining mastery of human nutrition requires a lot of dedicated time and focus. Even after 35 years in practice and a deep interest in health and diet, I do not consider myself to be a true expert. New information is published daily, and much of it is conflicting. And while virtually all experts agree that the SAD/WD is a driver of ill health, not all experts are united in their opinions of what constitutes the best diet to replace it with. Here are a few examples of common dietary approaches promoted by healthcare professionals:

Frequent Feeding: As mentioned above, many healthcare providers still advise their patients to eat small meals and snacks multiple times throughout the day. While this may help those with high-glycemic diets to avoid blood sugar crashes (more about that later), enabling them to manage their day with better energy, frequent eating/snacking drives weight gain and chronic diseases while turning off/down-regulating longevity genes. The Frequent feeding dietary approach also does not address the quality of a patient’s diet.

Cut Out Saturated Fats: Other health professionals advise their patients to reduce their intake of fats—especially saturated fats such as those found in eggs, red meat, and dairy—an approach based on data dating back to the 1940s when an association was first established between high consumption of these foods and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and certain cancers.

But despite decades of research, saturated fats have never been shown to cause CVD or cancer, and new evidence suggests that some types of saturated fat might be important for good health (more about healthy fats later). In addition, since many known problematic lifestyle behaviors including smoking, drinking, and consuming high amounts of processed foods tend to aggregate among high consumers of eggs, meat, and dairy (consider, for example, the quintessential SAD meal of a cheeseburger with fries, ketchup, and shake), it is impossible to tease out which among so many independent variables might be the driver(s) of ill health.

Eggs, meat, and dairy all feature consistently in the diets of people living in so-called Blue Zones—areas of the world where people routinely live past the age of 100. If such foods were the drivers of ill health and early mortality, we would expect them to be limited or absent from the diets of people living in Blue Zones. But from Sardinia to Loma Linda to Ikaria, people living in Blue Zones consume these foods (along with lots of fiber-dense vegetables, beans, and whole grains) as staples.

Vegetarianism and Veganism: Both vegetarianism and veganism are slowly gaining popularity in many parts of the developed world, including in the US. These diets have been associated with a mild reduction in cancer risk compared to the SAD/WD and have become more common among young people and those concerned about the environment and/or animal welfare.

In my view, there are compelling reasons to reduce or stop eating meat and animal products. The carbon footprint of animal agriculture is enormous and the cruelty endemic to animal farming is undeniable and disgusting. That said, the evidence does not support vegetarianism or veganism as the healthiest alternative for humans who evolved while eating animals and animal products along with a high-fiber plant-based diet. None of the world’s Blue Zones are vegetarian or vegan and, from a health perspective, while adding more plant foods to fiber-poor diets like the SAD makes complete sense, some of the best and most recent studies have failed to demonstrate that cutting out meat offers any significant benefits in terms of long-term health or longevity.

Eat Lots of Hearth-Healthy Whole Grains: Many cardiologists still promote a low-fat/high carbohydrate diet with lots of ‘heart healthy whole grains’ in the form of high glycemic foods like whole wheat bread, instant oats, and bran flake cereals which are loaded with rapidly digestible starches that cause blood sugar to spike after eating, ignoring decades of data which, if taken as a whole, roundly discredit the belief that such a diet will reduce their patients’ risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

When you take a grain, such as wheat, and then pulverize it into powder (flour) used to make bread or cereal, you destroy what is healthy in them. There are three parts of a wheat kernel: the bran, the endosperm, and the germ. The bran is the outer shell of the grain which is high in fiber and B vitamins. Inside the bran is the endosperm which is high in rapidly digestible starch. Deep to that is the germ, which, like the bran, is nutrient-dense. When making flour from whole wheat, the bran and the germ are removed (along with their fiber and nutrients), leaving only the endosperm whose rapidly digestible starch gets broken down quickly into glucose (sugar). Eating bread and cereals made from whole-grain flour is not the same thing as eating whole grains!

Eating whole grains results in a slow rise in blood sugar but eating flour-based foods made from the high-glycemic parts of whole grains, like the endosperm of wheat, causes massive blood sugar excursions. The best and most recent evidence suggests that increasing the consumption of things like whole wheat bread and cereals raises rather than lowers the risk of CVD.

The PURE (prospective urban and rural epidemiological) study, is a unique, long-running research project involving 225,000 participants followed in detail and 500,000 followed with simple information, currently being conducted in more than 1,000 urban and rural communities in 27 high, middle, and low-income countries. The PURE study is investigating the impact of modernization, urbanization, and globalization on health behaviors, including diet, to determine how they impact the risk of chronic diseases such as CVD, diabetes, brain health, and cancers. There is little question from the data gathered thus far that diets rich in high-glycemic foods promoted as ‘healthy options’ like whole wheat or whole grain breads, instant oats, and bran flake cereals are key drivers of all of these common diseases. And study after study after study has demonstrated poorer health outcomes among those on low fat/high carb diets compared to those on high fat/low carb diets.

Low Carb: And then there’s keto, Paleo, and other dietary approaches that have become popular in recent years… Low-carb or ‘ketogenic’ diets unquestionably help stabilize blood sugar and improve the sensitivity of our body tissues to insulin. For people currently eating a SAD, keto diets which are very high in fat, moderate or high in protein, and very low in carbs can be used to induce weight loss (up to a point) and reverse Type II diabetes. As mentioned above, study after study has demonstrated that low-carb/high-fat diets are superior to high-carb/low-fat diets, and this is true irrespective of caloric restriction. I have utilized them in my practice for years to help patients make dramatic health turnarounds.

But keto diets are also low in the healthy stuff found in plants such as fiber, resistant starches, and antioxidant polyphenols which we need to support and sustain long-term health. Over time, prolonged adherence to a keto diet can cause attrition of healthy fiber-loving bacterial populations in the gut, narrowing the GMB and setting us up for chronic diseases.

In my view, keto diets are a great tool but are best used in the short term for jump-starting fat loss, stabilizing blood sugar, and improving tissue sensitivity to insulin. In my practice, I often begin weight loss programs this way. Then, once blood sugar has been stabilized and patients are able to switch easily back and forth between burning fat and sugar for energy (i.e., once they are fat-adapted), I transition them to the HD for the long-term.

Paleo diets are closer to the EHD in that they promote the concept of eating as our ancestors did. But the specific ancestors targeted for emulation by this diet are those who lived in the Paleolithic era which preceded the agricultural revolution. As such, Paleo diets, like keto diets, prohibit the consumption of whole grains (such as farro, quinoa, and black rice), legumes (such as beans, chickpeas, and lentils), as well as dairy products (such as yogurt, kefir, and cheeses)—all foods that are staples in Blue Zones. And while some people have food allergies or sensitivities to components of these foods (such as gluten found in wheat, lactose in dairy, and lectins in beans and legumes), for most of us, these are particularly healthy foods loaded with fiber, indigestible/resistant starch (especially if prepared properly—but more about that later), healthy fats, and probiotic microorganisms (found in cultured cheese, yogurt, and other dairy products).

The restrictions imposed by Paleo diets are not based on scientific evidence but rather on a dogmatic principle of eating as our ancestors did before the agricultural revolution (about twelve thousand years ago). Paleo diets fall short in terms of both scientific validation and providing basic nutrition. What’s more, as with keto diets, Paleo diets are highly restrictive, making them difficult to maintain long-term.

I won’t unpack every popular diet here. Suffice it to say that each one I have investigated addresses some health-related issue(s) but not others. Even the so-called Mediterranean Diet (MD)—the only widely published diet strongly and consistently associated with better health outcomes—allows for the liberal consumption of high-glycemic flour-based foods and moderate amounts of added sugar. What’s more, there is poor consensus regarding what exactly constitutes the MD. That said, the MD, as it is variously defined, does tend to share more features of the Human Diet (HD) than any other popular diet.

In the final analysis, only the HD checks all the boxes: it supports a healthy GMB, avoids spikes in blood sugar (see the next section), and is sustainable over time. Now, let’s drill down into the HD in a little more detail…

The Human Diet (HD)

Human nutrition is a complex and evolving field but eating right doesn’t have to be overly complicated. You do not need to become encyclopedically knowledgeable about biochemistry, eat flavorless food, weigh serving portions, measure macronutrients, keep track of points, or commit forever to extreme restrictions that make dining out or attending social events stressful, to eat for optimal health, beauty, and happiness. Instead, you need only to understand and adhere to the following seven principles of the HD:

Principle 1: High in Naturally Occurring Fiber

It should come as no surprise by this point that the first principle of the HD is that it is very high in naturally occurring fiber. Remember that most of what our evolutionary predecessors ate and adapted to over millions of years was a diet rich in fiber-dense plant foods.

Without loads of dietary fiber and indigestible (resistant) starches, the GMB begins to contract as important bacterial species are pushed to extinction due to starvation. A contracted or narrow GMB has been implicated as a driver of a wide range of diseases. One reason the US bears an outsized burden of chronic illness compared to peer nations is that the SAD, which is low in fiber and resistant starches, has resulted in epidemic levels of gut dysbiosis.

How much fiber is enough? The general consensus is that we need at least 30 grams per day. But more is probably better as we will discuss when we get into specific meals, recipes, and shopping lists. For now, think of it this way: if most of the food on your plate (by weight) is made up of fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, legumes, and/or whole grains, you’re on the right track.

Principle 2: Low-Glycemic Index and Low-to-Intermediate-Glycemic Load (or the Concept of Slow Carbs)

The second principle of the HD is that all of our meals should be low-glycemic. Many of my patients are familiar with this term but what does it actually mean? To understand glycemic index and glycemic load, we need to first quickly review the biochemistry of carbohydrates.

Carbohydrates: There are three categories of macronutrients found in food: protein, fat, and carbohydrate. Carbohydrates (carbs) come in 2 main forms: simple and complex.

Simple Carbs: Defined as one or two sugar molecules bound together, simple carbs are also referred to as sugars. Sugars are absorbed easily into the bloodstream as glucose after a meal. Simple carbs like sucrose (table sugar), fructose (found in fruits and some vegetables), and high-fructose corn syrup (a combination of fructose and glucose) are abundant in the SAD. When we eat foods loaded with simple carbs, our blood sugar levels rise very quickly causing what is commonly referred to as a blood sugar spike. The faster blood sugar goes up after eating a particular food, the higher its glycemic index (GI). We can think of food made with simple carbs as high GI foods or fast carbs.

Complex Carbs: Defined as three or more sugar molecules bound together, complex carbs are also commonly referred to as starches. When we eat starches, it takes some work and time for our bodies to break them down into absorbable sugars and non-absorbable fiber, so blood sugar rises less quickly but over a longer period of time after eating complex carbs compared to simple carbs. For this reason, some complex carbs can be thought of as slow carbs. In fact, complex carbs are a little more, well, complex than that, because not all complex carbs are starches, and not all starches are slow carbs. Hang in there, it gets easier soon…

Starches: The two main versions of dietary starch are amylose and amylopectin. Amylose, a single-chain starch, is hard to break down into sugar while amylopectin, a branched-chain starch, is much more easily digestible. We’ll get into this in a little bit more detail later on but for now, let’s just make a note that foods high in amylose are generally referred to as indigestible or resistant starches. And, as with fiber, resistant starches are slow carbs. By contrast, foods high in amylopectin are generally referred to as rapidly digestible starches, and rapidly digestible starches are fast carbs.

Like fiber, resistant starches feed friendly bacteria in the GMB. Because our bodies have a hard time digesting these slow carbs, they serve to bulk up stool for better elimination, do not cause a significant rise in blood sugar, and contain few usable calories, so eating them helps us to feel full while avoiding weight gain. Slow carbs, either in the form of fiber or resistant starch are staples of Blue Zones and of the HD.

Beans, legumes, and many whole grains contain high amounts of fiber and amylose-dominant (resistant) starch. They are slow carbs but how they are prepared affects just how slow they are. Cooking some of these foods alters their chemical structure, turning resistant starch into rapidly digestible starch, and thereby downgrading them from healthy (slow) carbs to unhealthy (fast) carbs. For example, potatoes are rich in resistant starch, but cooking them changes that starch into a digestible form that can cause blood sugar to soar after eating. That’s not good but there might be a way around this problem if you want to include some potatoes in your version of the HD which we will discuss later.

Fiber: Fiber is classified as a complex carb even though it does not contain sugar molecules and is, therefore, not a starch. Our bodies cannot digest or absorb fiber, so eating foods high in fiber generally results in an even slower and smaller rise in blood sugar compared to foods high in resistant starch.

Okay, with that very basic but important understanding of the biochemistry of carbs under our belts, let’s now turn our attention to the first two principles of the HD:

Eat lots of fiber.

Eat foods with a low glycemic index and low to intermediate glycemic load (AKA slow carbs).

The Glycemic index (GI) of a food is a measure of how quickly blood sugar (glucose) goes up after eating a serving of it. Foods and drinks that are high in simple carbs and rapidly digestible starch such as bread, chips, tortillas, and most baked goods (including things like gluten-free and whole wheat bread), cause blood glucose to shoot up quickly. That means they have a high GI. By contrast, foods rich in fiber and resistant starch, such as beans, farro, and black rice cause a comparatively small and slow rise in blood sugar (i.e. they have a low GI).

High-GI foods are fast carbs; intermediate-GI foods are intermediate carbs; and low-GI foods are slow carbs.

GI is measured on a scale from 0 - 100 with glucose as the reference standard (the GI of glucose = 100). The system of GI classification is as follows:

Low-GI: ≤55

Intermediate-GI: 56-69

High-GI: ≥70

Blood sugar levels are tightly regulated in the body. When blood glucose rises after a carbohydrate-containing meal, our bodies release a hormone made in the pancreas called insulin to bring it quickly back down to normal. When blood sugar dips too low, the pancreas releases a different hormone called glucagon which stimulates the liver to release its stored sugar into the blood to bring it back up to normal.

Maintaining normal blood sugar levels is an essential part of physiological homeostasis as the diagram below shows:

Blood Glucose Level Regulation under Negative Feedback System. Credit: Shannan Muskopf – Biologycorner.com

How much insulin we release after a meal depends in part on the GI of the foods we eat. Fast-carb foods like soft drinks, chips, and bread are newcomers to our evolutionary story and we are not yet biologically well-adapted to them. When we snack on a bag of chips or down some Gatorade while we work, our blood glucose spikes, triggering a kind of panic response from the pancreas which over-secretes insulin in anticipation of extreme, potentially dangerous levels of sugar intake. Remember, throughout our evolutionary history, the sugariest things humans ate were fruits and berries. The GI of berries ranges from 28 - 40; the GI of Gatorade is 89 and the GI of whole wheat bread is 78!

The main job of insulin is to bring blood sugar down, but this panic response to fast carbs, known as insulin overshoot, ends up driving blood sugar down too much. For most of us, an occasional insulin overshoot can be tolerated without any ill health effects other than perhaps feeling sleepy a couple of hours after eating. But chronic low blood sugar caused by insulin overshoot makes us crave fast-carb foods and can lead to a kind of vicious circle in which we eat fast carbs that spike blood sugar, suffer insulin overshoot which pushes blood sugar too low causing us to crave more fast carbs, and then repeating the cycle all over again. This can happen even when someone keeps their energy intake in balance with their energy consumption, avoiding weight gain. High consumption of fast carbs in thin-bodied endurance athletes can lead to diabetes and heart disease among persons who appear to be in excellent health.

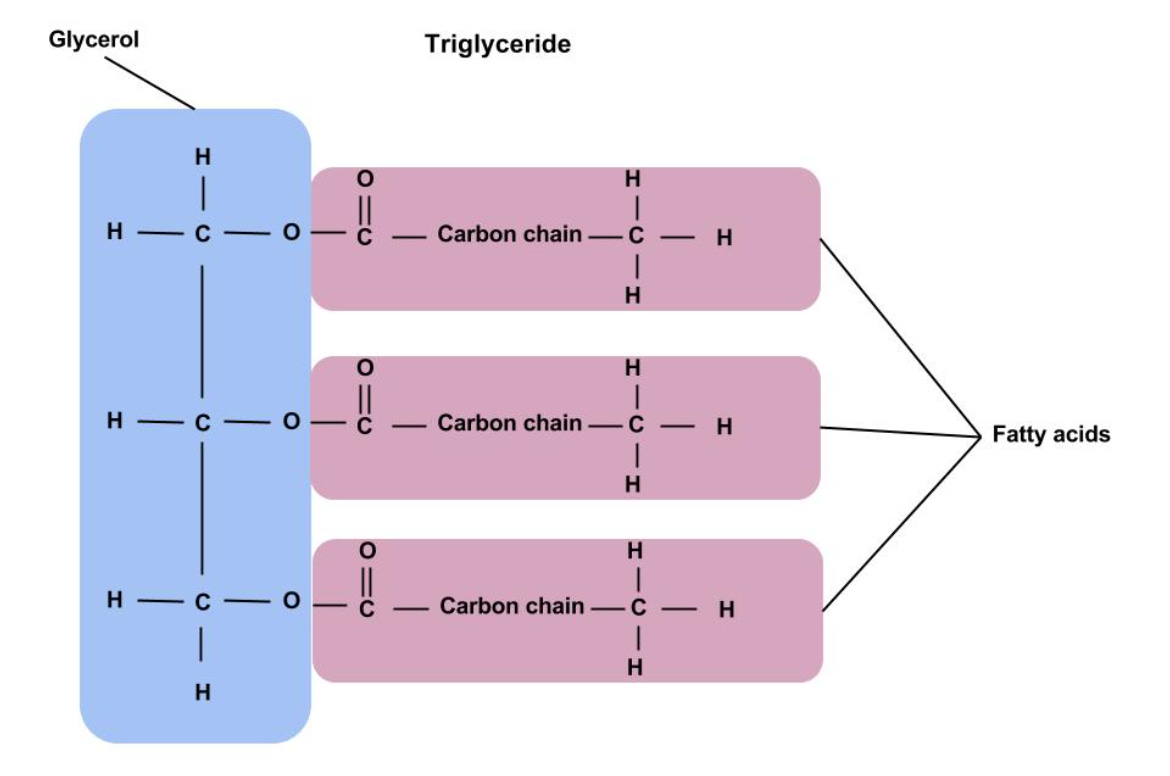

Insulin drives blood glucose down by moving it into the liver and muscles where it gets stored as glycogen. Glycogen can be thought of as our chief energy reserve. However, if the liver and muscle tissues are filled to their capacity with glycogen, insulin converts blood glucose into fat (triglyceride) instead and stores it in adipose (fat) tissue. Adipose tissue can be thought of as our backup energy reserve.

Importantly, insulin not only drives fat storage but also blocks fat burning. That is why eating fast carbs makes it so easy to gain weight but also so hard to lose it. The excess insulin that hangs around after overshoots makes it almost impossible to mobilize stored fat for energy.

A diet like the SAD/WD, rich in fast carbs, spikes blood sugar several times per day, leading to chronically elevated levels of insulin, and making it almost impossible to lose weight. And, in addition to storing and protecting our fat, insulin also induces blood vessels to constrict which can raise our blood pressure.

Too much insulin drives our blood sugar too low, causing extreme hunger, irritability, fatigue, light-headedness, and uncontrollable cravings for more fast carbs, making it nearly impossible to fast (we will address fasting soon but for now, remember that feasting and fasting was the pattern of eating by which our bodies evolved over millions of years). At the same time, it protects stored fat from being burned for energy, blunting our attempts to lose weight. Perhaps worst of all, prolonged exposure to insulin from repeated overshoots caused by a diet like the SAD/WD which is rich in fast carbs makes our body tissues grow less sensitive to its blood-sugar-lowering action over time, forcing the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas to work harder to pump out even more insulin. This also creates a vicious circle that can lead over time to beta cell fatigue and insulin resistance, setting the stage for diabetes.

When our tissues become insulin-resistant, our bodies struggle to properly regulate blood sugar levels after eating fast carbs. This puts pressure on the beta cells to make even more insulin. Chronically high insulin levels in the context of repeated blood sugar excursions drives the development of something called metabolic syndrome which is the first step toward diabetes and other chronic diseases.

Metabolic syndrome (MSy) includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist and deep in the abdomen, and abnormal cholesterol levels. MSy increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes. But aside from a large waist circumference, most of the problems associated with metabolic syndrome have no signs or symptoms. Many people have metabolic syndrome without even knowing it and are stunned to learn that they are pre-diabetic, hypertensive, or have dysregulated blood sugar and/or blood lipids after having routine blood work at an annual check-up.

High blood pressure, high blood sugar, obesity, dyslipidemia, CVD, and diabetes—for decades we observed that these were co-morbidities, often aggregating together in the same patient. Now we understand how a diet rich in fast carbs can drive all these problems by triggering the overproduction of insulin. And that’s not even the whole story. Spiking blood sugar with fast carbs also triggers a cascade of inflammatory changes that lead to arterial wall injuries and the accumulation of something known as advanced glycation end products (AGEs) also called arterial plaques…

In a sense, GI can be said to measure the quality of carbohydrates in a particular food with slow carbs (low GI) being high quality and fast carbs (high GI) being low quality foods. GI is an important metric when deciding which foods to include in or exclude from a healthy diet. Virtually no high-GI foods can be found in nature and the HD excludes high-GI foods. Some amount of intermediate GI foods can be tolerated but low GI foods are clearly preferred and form the bulk of the HD.

Glycemic Load: GI is not the only metric we use to understand the health impact of carbohydrate-containing foods. Another important metric a food’s glycemic value is its glycemic load (GL). A food’s GL is obtained by multiplying the quality of carbohydrates in a given food (the GI) by the total number of carbs (in grams) contained in a serving of that food and then dividing by 100. The system of GL classification is as follows:

High-GL ≥ 20

Intermediate-GL = 11-19

Low-GL = 10 or less

If GI tells us how fast blood glucose will go up after eating something, GL tells us how long blood sugar will remain elevated above the baseline after the meal. Many health and nutrition experts are now incorporating GL as a key metric for evaluating the healthiness of foods, especially among patients with or susceptible to metabolic syndrome and diabetes.

The HD is made up mainly of low GI and low or intermediate GL foods. The good news is that knowing which foods conform to those parameters is not very difficult. Virtually every whole (unprocessed) food that comes from nature is included in the HD. Keep reading, we’re more than half-way to the finish line of understanding the all-important role of GI and GL.

Some practical examples

Now, let’s look at specific examples of how to use GI and GL to determine whether a food is healthy or unhealthy. Canned cannellini beans have a GI of 31, making them a slow carb. So far, so good. And they are low/moderate in total carbs, about 15 g per serving. We would calculate the GL of canned cannellini beans as follows:

31 (GI) x 15 total carbs per serving (in grams) divided by 100 = a GL of 4.65.

Since low GL is ideal (low = 10 or less), we can say that canned cannellini beans, which are low in both GI and GL, are particularly healthy. They are also high in fiber and indigestible starch which raises their health value further still. Beans are not a very old food to which we became adapted over our evolutionary history, but they are filled with the things that our bodies learned to make good use of. As such, they are not part of the EHD but they are a staple of the HD (as they are in the world’s Blue Zones).

Side note: Cooking dried beans from scratch and rinsing them well with cold water to get rid of excess starch and lectins is a superior way to prepare them compared to canned beans. It further reduces the GI and GL, and eliminates most of the compounds that can cause some people to experience gastrointestinal distress after eating beans and legumes. I will speak more about this and other cooking methods to maximize health later but for now, let’s tuck away the idea that beans are rich in fiber and resistant starch, low in GI and GL, and preparing them correctly makes them more delicious and one of the healthiest foods that we can eat. If there is a single food that is consistent between the world’s six Blue Zones, it’s beans.

Now, let’s compare cannellini beans to another staple of the HD, black rice. Black rice (also known as forbidden rice) has a GI of 42 which makes it a slow carb (<55). But it is higher in carbs than beans with about 34 g per serving. We calculate the GL of black rice as follows:

42 (GI) x 34 (grams of carbs) divided by 100 = 14.3 GL (intermediate = 11-19)

Black rice will not cause blood sugar to spike and will, therefore, not induce insulin overshoot. It has a fair amount of fiber and a lot of resistant starch to feed the GMB. Black rice is a slow carb (low GI) with an intermediate GL. It raises blood sugar gradually for a prolonged period of time, making it particularly good for long-term energy. Experts who advocate for only low GL foods, such as those who promote a keto diet, would exclude black rice but it is an extremely healthy food and a staple of the HD. Importantly, as with beans, it lends itself to being mixed with other healthy foods as part of a well-balanced meal (I refer to this as a foundational element of the HD) as we will see later.

We’ve reviewed two HD staples: cannellini beans and black rice. Now, let’s look at another food—one that is not generally included in the HD: white rice. White rice has a GI of 80 which makes it a fast carb (≥70) and has about the same number of carbs per serving as black rice (35 g). Let’s calculate its GL:

80 (GI) x 35 (grams of carbs) divided by 100 = 25 (high = 20 or more)

White rice is a fast carb (high GI) that causes a large, sustained blood sugar excursion (high GL). It contains about one-fifth the amount of fiber compared to black rice and, when cooked, is made up mainly of rapidly digestible starch. Eating a bowl of white rice will spike blood sugar and lead to insulin overshoot without providing nearly the level of fiber or nutrients.

Side note: brown rice is a little better than white rice with a GI of 58 (intermediate). It has 34 g of carbs per serving, giving it a GL of 20 (borderline high). So brown rice doesn’t make the cut for inclusion in the HD but it’s less harmful than its white rice cousin.

Before we move on, let’s add one other foundational element of the HD to the conversation. One serving of cooked farro contains a whopping 7 g of fiber. It has a low GI (45) and 37 g of total carbs which gives it an intermediate GL value of 13.5. Like black rice, farro is full of nutrients while remaining a low-glycemic food and it mixes well with other healthy foods making it a foundational element of the HD.

The HD is rich in foods that have low GI, low/intermediate GL, and are high in fiber and/or resistant starch.

Principle 3: Frequently Add Fermented Foods

Fermentation is the process of converting carbs into alcohol or organic acids (like lactic or butyric acid) using microorganisms such as bacteria or yeast under anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions. While most of us are familiar with the fact that wine and beer are fermented beverages, we don’t always think about the many foods and drinks we consume including yogurt, aged cheese, kimchee, olives, pickled vegetables, and kombucha that are also fermented and teeming with healthy bacteria for our GMB.

As discussed in detail in the April 25, 2022 Briefing, for the GMB to be strong and healthy, it must be deep and wide. Depth refers to the number of microorganisms in the microbiota while width refers to the number of different species of microorganisms—especially of healthy bacteria. Throughout most of evolutionary history, our human ancestors swallowed microorganisms every time they ate or drank and the GMBs of our hunter/gatherer forebearers were extremely deep and wide.

But over time, as we learned to grow and store our food and were able to increase our consumption of animal meat, vegetables, and processed grains that were higher in rapidly digestible starches such as breads, cereals, and other foods made from flour, the amount of fiber and resistant starch in our diets decreased and so did the depth and breadth of our GMBs. Sanitary measures such as washing and fully cooking our foods further lowered our consumption of live environmental microorganisms, making the GMBs of our more recent ancestors narrower and shallower still.

Over the last hundred or so years, things have gone from bad to worse when it comes to nutrition. The highly sanitized, processed and ultra-processed foods of today’s SAD are mostly very high-glycemic, fiber-free, calorie-dense, and nutrient poor. Is it any wonder that we are the fattest country on earth?

Let’s take a minute to solidify our understanding of why this has happened. As stated previously, a strong GMB is essential to our health. As described beautifully in The Good Gut (Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health) by, Justin and Erica Sonnenburg, perhaps the most important feature of a healthy GMB is diversity. Healthy people with stable blood sugar levels and low amounts of central or visceral fat (fat stored in the abdomen and around our internal organs) tend to have widely diverse GMBs with several hundred different species of bacteria coexisting in their colons. By contrast, less healthy people with high amounts of central and visceral fat tend to have far shallower and narrower GMBs.

As the EHD changed over time from hunter/gatherer societies through the agricultural revolution and the introduction of flour, to the mass production of food, until the present day SAD loaded with refined, high-glycemic, processed foods manufactured to be delicious and addictive, we can trace a progressive narrowing of the human GMB, with sequentially lower degrees of bacterial diversity, especially in developed societies like ours:

Perhaps the most important human (prospective) study to date, comparing the effects of high fiber and high fermented food diets, showed that the group who were switched from a SAD/WD to a high-fiber HD without fermented foods increased their nutrient profile and expanded the depth (although not so much the breadth) of their GMBs. Deepening the GMBs led to an increase in certain health-giving metabolites as well as a decrease in toxic ones.

In addition, subjects in that high-fiber cohort who began the study with at least a moderate breadth of bacterial species (intermediate or better GMB diversity) showed a significant lowering of inflammation. However, those who started the study with low bacterial diversity (a narrow GMB) actually showed an increase in inflammation when moved to a high-fiber diet as the sole intervention. Not enough fiber-fermenting bacteria in the GMB makes a high-fiber diet difficult to handle and can cause GI distress. In my practice, I have noticed that patients with obesity often cannot tolerate a sudden shift to a healthier high-fiber diet without also adding fermented foods (read on).

By comparison, the second study group which was switched from a SAD/WD to a high-fermented food diet (yogurt, kefir, kimchee, sauerkraut, etc.) without adding extra fiber, demonstrated some increase in depth and a strong increase in the breadth of their GMBs, steadily increasing the number of different bacterial species by 25% over the four-month study period. And all the participants in this group showed a lowering of inflammation.

Interestingly, it turned out that just a small percentage (about 5%) of the new microbes found to have taken up residence in the GMBs of this cohort came directly from the fermented foods themselves. Most (95%) of the new species did not come directly from the fermented foods that they ate. It appears that frequent consumption of small amounts of fermented foods increases the diversity of the GMB by making it more generally friendly to the process of colonizing new fiber-fermenting species.

So switching from the SAD/WD to the HD which is high in both fiber and resistant starch (slow carbs), low in sugar and rapidly digestible starch (fast carbs), and promotes the frequent consumption of fermented foods, stabilizes blood sugar, lowers inflammation, enables fat burning (by lowering insulin levels), and expands the depth and breadth of the GMB which is critical for health and longevity. What’s more, we can see a shift in the GMB begin to take place in just a matter of days after making the switch to the HD, and achieve, on average, a 25% increase in GMB breadth in a matter of just a few months.

What About Probiotic Supplements?

One would expect, based on the data from the fermented food cohort of the previously described study, that taking probiotic pills, which can supply the gut with higher concentrations of healthy bacterial species than a serving of fermented food can, would have an even stronger health-enhancing effect on the GMB compared to merely adding frequent tastes of pickled vegetables, yogurt, and kimchi to meals. However, a major double-blinded, placebo-controlled) study conducted on patients with metabolic syndrome, showed no improvements in GMB depth or breadth from taking probiotic supplements, nor was there any reduction in inflammation or any improvements in blood lipids, blood sugar, or insulin levels. In fact, patients with metabolic syndrome, on the whole, did not seem to benefit at all from high-dose probiotic supplementation!

Interestingly, on deeper analysis of that study’s data, it was observed that within the treatment group (but not the control group who did not have metabolic syndrome), about half of the subjects given probiotics actually showed an increase in inflammation, triglycerides, and blood sugar while the other half did show some benefits—the two groups seemed to have canceled each other out in the study’s final results. What was the difference between those who were made slightly worse and those who reaped a small benefit from probiotic supplementation? Unlike in the prior study, where the differentiating factor between those who showed increased or decreased inflammation after being switched to a high-fiber diet was their baseline GMB diversity, in the probiotic supplement study, what made some patients respond to the treatment was that (without being asked to do so) the responders had started to include more fiber in their diet while they were taking the probiotics. In other words, they accompanied the probiotic supplements with prebiotics (high fiber foods).

It may be that switching from a SAD/WD to a high-fiber diet combined with probiotic supplementation could be of slightly more benefit than just the dietary intervention of increasing fiber intake alone. It might also reduce the gastro-intestinal discomfort experienced by people with narrow and shallow GMBs when they add more fiber to their diets. We don’t have the data to make that case yet. But we do have data on combining high fiber diets with fermented foods and it is stunning (keep reading, we are going to come back to this).

The best and most current research is telling us that small bites of pickled and/or fermented foods containing live probiotic microorganisms in conjunction with a low-glycemic, high-fiber diet appears to be a clearly superior and far less expensive approach to improving gut health and general health compared to taking probiotic supplements. I have, in fact, stopped recommending or selling probiotic supplements in my practice.

Principle 4: Fast Routinely

The fourth principle of the MHD is to fast routinely. Fasting means taking in no (or virtually no) calories for at least 24 hours. It is well established that fasting initiates two extremely healthful physiological processes:

1) Autophagy: As mentioned previously, autophagy is the adaptation that our bodies developed to derive health benefits from periods of food scarcity—a fact of human life throughout our entire evolutionary history until about 100 years ago. Winters, dry spells, rainy seasons, and migratory/hibernation patterns of animals all conspired to force upon our ancestors the practice of fasting. Over a great expanse of time, we adapted to fasting by initiating a physiological process of cellular cleansing and self-repair.

During autophagy, which is widely believed to begin at about 24 hours without calories (a little sooner for some, a little later for others), our cells begin to form structures called autophagosomes. Autophagosomes act like vacuum cleaners, sucking up cellular debris such as old proteins that have grown too stiff to fold themselves into useful shapes, and breaking them down for energy.

Like the energy stored in the liver as glycogen or in adipose tissue as triglyceride, old, non-functional proteins represent a kind of third energy repository. As with purging visceral fat, cleansing our cells of these low or non-functional proteins improves our health. It rejuvenates our cells while releasing needed energy through a process that helps keep our metabolism high when we fast. Fasting is an essential part of my anti-aging strategy.

2) Fat burning: Our bodies have two main fuel sources: sugar and fat. When we eat diets rich in carbohydrates—especially fast carbs—our bodies choose to run on sugar because doing so is easier. But if there are no readily available carbs to eat and we start to run out of glycogen reserves in our liver and muscles, our bodies default to fat burning as their primary source of energy.

For those who are not fat-adapted (able to switch easily back and forth between using fat and sugar for energy) from having been on a ketogenic diet for some time, fat burning generally begins around the time when we enter the fasting state (at about 24 hours without calories) when most of the liver’s glycogen stores have been depleted. But exercising while fasting can dramatically jump-start fat burning. Glycogen stores deplete after about 1 - 1.5 hours of steady moderate exercise, such as hiking or jogging and, although it may be counterintuitive, getting a workout in on fasting days actually improves the fasting experience by boosting energy and mental clarity through inducing ketosis (fat burning). Fat molecules contain more energy than sugar molecules so ketosis provides us with a lot of energy. I like doing several short bursts of intense exercise (2-4 minutes) during my fasts, especially if I feel my energy dipping, and enjoy the mental clarity, feeling of vitality, and burst of alertness that doing so provides.

Fasting v. Intermittent fasting

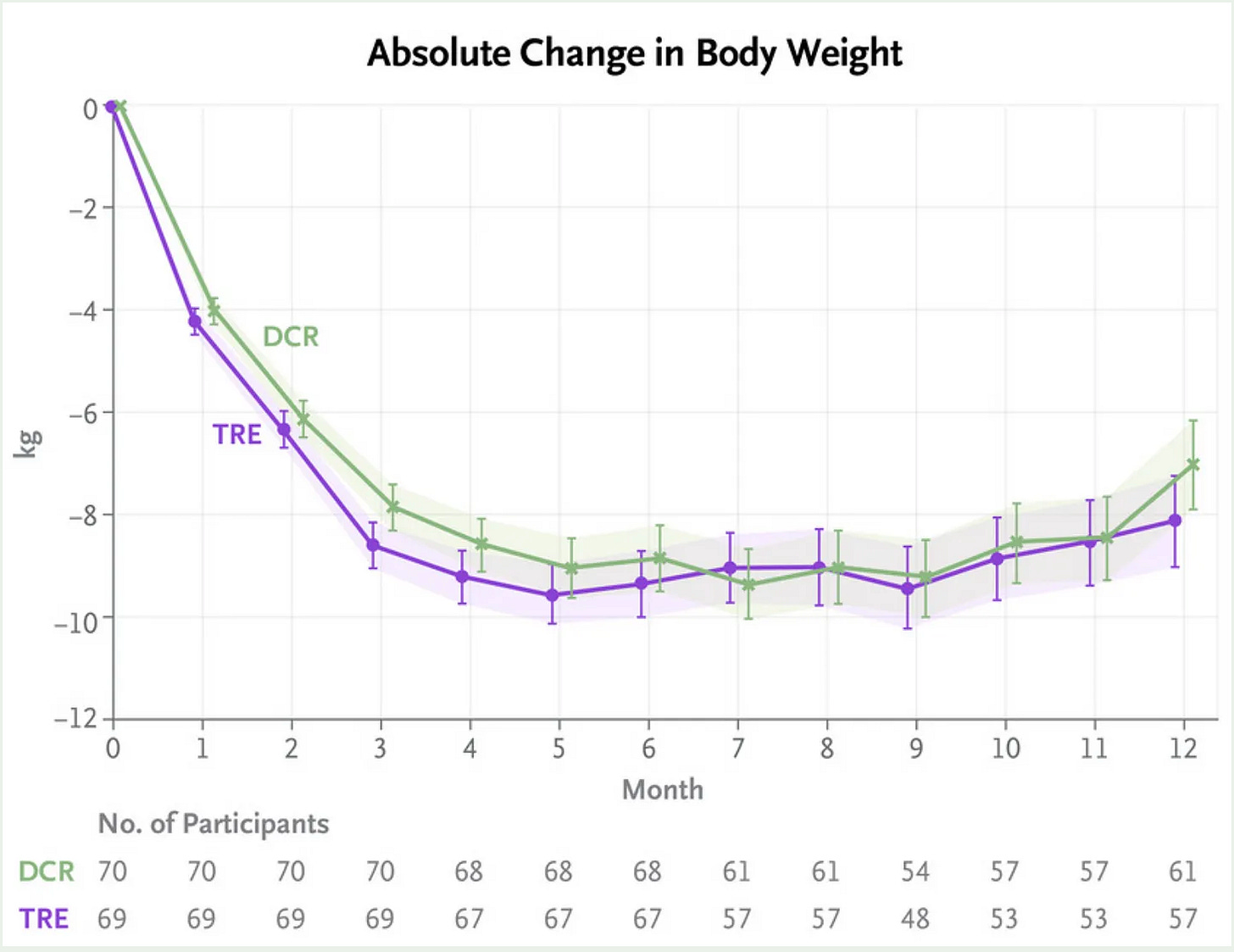

Decreasing caloric consumption by skipping one or two meals a day, commonly referred to as time-restricted eating or intermittent fasting, can induce weight loss and lower insulin levels (provided we don’t compensate calorically for skipped meals by overeating when we do eat) which are major health benefits. At least, for a while. But over time, our bodies begin to adapt to chronically reduced caloric intake by slowing down our metabolic rate. Our bodies learn to make do with fewer calories by becoming more efficient at extracting them from the limited amount of food that we are eating during intermittent fasting. As our metabolism slows down to align with the new reality of mild-to-moderate food scarcity, fat burning becomes unnecessary and, typically after about 3-5 months of intermittent fasting, weight-loss grinds to a halt.

Once this takes place, we are now in a pickle. We’re no longer burning fat on our calorie-reduced diet so we stop losing weight. In fact, typically at about 9 months into time-restricted eating/intermittent fasting, we will start to see weight beginning to creep back up. Worse than that, months of calorie restriction induces a permanent state of sluggish metabolism. If we then return to eating 3 (or 4-6) times per day, raising our caloric intake back to ‘normal', we will gain weight quickly. Eating the same amount of calories that used to sustain us without causing weight gain before starting intermittent fasting, when our metabolic rate was higher, now the effect of overeating in the context of a slower metabolism. Our metabolism slows down with prolonged caloric restriction (dieting or intermittent fasting) but does not speed back up when we return to eating more calories!

Amazingly, by contrast, fasting (24 or more hours without calories) does not slow our metabolism at all. At about the same time that we begin to induce autophagy, we actually experience a small boost in metabolism. Cleaning up or replacing old, senescent cells is hard work which keeps our body’s metabolism high, enabling us to lose fat through fasting without saddling ourselves with a permanently slowed metabolic rate. And activating cellular self-repair mechanisms through autophagy enables us to avoid stretch marks and sagging skin as we lose weight.

The HD includes regular fasting, at least once per week for a minimum of 24 hours, keeping in mind that, since autophagy begins at around that time, each hour beyond 24 hours without calories is an hour during which autophagy is taking place. I fast twice per week, typically going about 26 - 28 hours on one of the days and 36 or more hours on the other. There are some data to suggest that fasting while sleeping induces even more autophagy, so the practice of not eating from breakfast one day to lunch the next represents an ideal fast in terms of providing health benefits.

Principle 5: Mix It Up

One of the striking dietary similarities among those living in Blue Zones is that they tend to not only eat lots of fiber-dense plant foods like beans, lentils, farro, berries, fruits, and vegetables, but they often mix them together in a kind of smorgasbord of shapes and colors.

Earlier in this Briefing, we broke down the GI and GL of a few particularly healthy foods: cannellini beans, black rice, and farro. These are foundational elements of the HD because they are loaded with fiber and resistant starch which our GMB needs to maintain healthy bacterial depth and breadth. And, because they are relatively low glycemic foods, they don’t initiate inflammation-causing blood sugar spikes or provoke insulin-overshoot that, over time, nudges us toward metabolic syndrome. Now, consider the following dish that I made this morning:

Into a rice cooker add two cups of well-rinsed black rice. Add a nice pour of extra virgin olive oil or a knob of organic butter. Add one cup of raw almonds, one cup of raw pumpkin seeds, and a dozen dried sour cherries, chopped. Add bone or vegetable broth of your choice and hit start…

The resultant foundational element can be mixed with or added to in myriad ways to create meals that are nutrient and fiber-dense while being calorically and glycemically low. I plated the foundational element, adding some pomegranate seeds, kimchee (for the probiotics), roasted broccoli, and a fried egg. Here was Tricia’s and my breakfast this morning:

Notice the kimchee (made here using cubed radishes) is not a true serving but just a taste. The data suggest that it is not the volume of probiotic microorganisms consumed in a meal that shifts the GMB toward better diversity but rather the frequency with which we expose the GMB to something teeming with healthy microbes.

In fact, each whole food ingredient in this dish, except for the foundational element (the black rice), is present in small (less than a full serving) amounts, including the nuts, seeds, and bits of dried fruit that were cooked in with the rice. This smorgasbord of a dish is loaded with wonderful things—protein, fiber, resistant starch, probiotic microbes, vitamins, minerals, inflammation-lowering polyphenols, healthy fat, etc. (more about some of these things later). If the foundational element is made ahead of time (I make a large amount of a dish like this one typically twice per week) and stored in the fridge, assembling creative meals using whatever happens to be on hand is rather easy. That meal took less than 10 minutes to cook.

Notice also all the colors (green, red, orange, purple, magenta, and white). Lots of colors means lots of different nutrients were packed into this meal which was a delicious, and texturally enjoyable blend of umami, sweet, tart, salty, briny, nutty, crunchy, creamy, and chewy. Our blood sugar rose slowly and smoothly after this breakfast and remained slightly elevated for quite a while, providing us with excellent energy for the hike we took a couple of hours later.

Mixing up your plate with lots of different high-quality foods of different colors and textures improves both the quality of the meal and the eating experience. It makes things more appealing to the eyes and fills the palate with the subtle deliciousness of healthy foods.

Pleasure-seeking v. happiness-seeking

Training ourselves to prefer foods that are subtly rather than overpoweringly delicious is a central concept of the HD. We have been marketed to love and crave hyper-palatable foods engineered to have more flavor than anything nature provides. Such foods push pleasure buttons in our brains that release a hormone called dopamine. When we eat these processed, ultra-pleasure-producing foods on a regular basis, they get their hooks into our brains, creating what I refer to as a ‘soft addiction’ marked by craving, fantasizing, and seeking behaviors that nudge us robotically from our desks (or our beds) to snack, even when we are not really hungry. For many of us, eating has become as much about pleasure-seeking as quelling hunger. But compulsively eating/snacking for pleasure makes us fat, sick, and tired.

Once we develop a soft addiction to hyper-palatable processed foods, it becomes difficult to derive enjoyment from healthy foods like berries, which are subtly sweet, or black rice with its delicately understated umami. Natural whole foods do not come close to packing the pleasure punch of ice cream or MSG-laced nacho cheese-flavored tortilla chips. A trap has been set for us by a Big-Food corporate culture, the goal of which is to maximize profit for them at the expense of public health and happiness. And we, as Americans, have collectively walked right into it.

Calorically dense, nutrient-poor, high-glycemic fast food are foundational elements of the SAD. Recent data show that more than a third of American adults eat fast food on any given day and younger Americans are the biggest consumers with 45% of adults between the ages of 20 - 39 eating some fast food every day. Feeding a processed food addiction through pleasure-eating moves us away from our health and beauty, away from our happiness, and toward obesity and chronic illness…

But there is good news; it takes just 30 days on the HD to calm the cravings for processed, hyper-palatable junk foods, and for our palates to regain the ability to start appreciating the subtly beautiful flavors of fresh, natural foods again. A salad, like the one pictured below, made with a mix of raw diced zucchini, cilantro, purple cabbage, butternut squash, chickpeas, and crushed almonds, dressed with unfiltered olive oil, white balsamic vinegar, salt and pepper, and a squeeze of lemon is pretty to look at, subtly delicious, low in calories, and packed with fiber, resistant starch, and all kinds of antioxidant phytonutrients. Dishes like these are common in Blue Zones. Add a glass of sparkling water topped off with guava kombucha for some probiotics, and you’ve got a perfect HD lunch.

Principle 6: Eat Good Fat

While the simplistic mantra to cut out fat to improve health has been more-or-less debunked, and most nutrition and health experts now talk about good and bad fats instead, it has not been established just how much good dietary fat each day is optimal for our health. In fact, an ideal diet is probably not based on some preset amount but on incorporating some high-quality fat while keeping an eye on overall daily caloric consumption.

Here’s how I look at it: Good fat is essential for our health but it is also the most calorically dense of the macronutrients. Protein and carbohydrates each contain 4 calories per gram while fat contains 9 calories per gram (remember that fat molecules store more energy than sugar molecules which is why we feel so much energy on a keto diet). When we consume more calories than we burn in a given day, our bodies store the extra energy mainly as fat (triglyceride) in adipose tissue around the waist and deep in our abdomens, around the visceral organs. Adipose cells in the visceral storage compartment are metabolically active and when they swell with fat, they make pro-inflammatory hormones that work against our health and longevity. I’ll be talking about this later in more depth but for now, let’s just make a note that generally speaking, the more (healthy) fat I add into a meal, the smaller I make my serving size to avoid taking in too many calories.

So, which fats are healthy and which are not? What seems to be true has changed a lot over the last three decades but before we start naming names, we’ll need to do a quick overview of dietary fat.

Saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats (the good, the bad, and the ugly)

The fat in beef and pork (think of the white rind around a ribeye steak or pork chop) is a form of saturated fat. Chemically, saturated fats have no double bonds in their carbon chains making them solid at room temp. By contrast, polyunsaturated fats such as vegetable and seed oils, have multiple double bonds in their carbon chains which makes them quite liquidy at room temp. Olive oil, a monounsaturated fat with just one double bond in its carbon chain, is somewhere in between; it pours at room temp but more slowly than its watery polyunsaturated cousins.

When I was in school 35 years ago, the received wisdom was that the more solid a fat was at room temperature, the more unhealthy it was to eat. Back then, the belief was that absorbing the cholesterol and triglycerides of saturated fat into the blood after a meal would cause them to stick to the walls of our arteries and/or form clumps capable of clogging up our blood vessels.

Today, we know that this plumbing model isn’t how things work. And we also know that the categorical prohibition against eating saturated fats was premature and incorrect. In fact, as the famous randomized, controlled Women’s Health Initiative Study demonstrated on more than 160K women over seven years, reducing saturated fat intake by two-thirds did not lead to any weight loss or any reduction in their risk for various disease endpoints including strokes, heart attacks, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer.

And The Sydney Diet Heart Study showed that men who replaced saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, despite seeing a lowering of their LDL (bad) cholesterol, actually experienced an increase in heart attack risk of 60% and an increased risk of death from any cause (all-cause mortality) of 70%!

In 2016, the results of the Minnesota Coronary Experiment performed at the Mayo Clinic were finally published, showing that among hospital in-patients and residents of nursing homes, replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat again lowered LDL cholesterol but dramatically increased those patients’ risk for heart disease and all-cause mortality.

Eating a diet low in saturated fat can no longer be considered a rational health recommendation and replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat is a bad recommendation.

Intuitively, these recommendations, which are still promoted by many healthcare professionals including some cardiologists and dieticians, always seemed specious to me. Why? Because regular consumption of saturated fat is an essential part of the diet in every Blue Zone and has been part of the EHD for more than 2 million years. We should be well adapted to it by now. And it turns out that we are.

We now know that most saturated fatty acids with an even number of carbon atoms in their chemical chain (even-chain fatty acids), such as stearic acid and oleic acid, tend to drive up inflammation, and that chronic inflammation increases our risk for chronic diseases. But we also know that odd-chain saturated fatty acids such as pentadecanoic acid and heptadecanoic acid found in dairy products and coconut oil tend to lower inflammation and reduce our risk of chronic diseases. So, does that mean we should consume very high amounts of odd-chain saturated fatty acids and completely cut out even-chain saturated fatty acids?

Well, for one thing, many foods rich in saturated fats contain both. For example, red meat and dairy contain about equally high amounts of odd and even chain saturated fatty acids. We also know that some even chain saturated fatty acids (such as butyric acid found in meat) actually lower inflammation instead of raising it. The more we learn about how our bodies work, the more it becomes clear that health is about balance, not categorical binaries such as don’t eat saturated fat/eat lots of saturated fat, or don’t eat pro-inflammatory fat/only eat anti-inflammatory fat. Instead, what seems to be true is that ideally, we want a balance of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory saturated fats.